When will the next big earthquake hit? With major fault lines in California, it’s not a matter of if, but when. Learn about fault line cycles, signs of movement, and the interval between major earthquakes along the Hayward fault.

What Exactly is ‘The Big One’ Earthquake?

‘The Big One’ earthquake refers to a quake of 7.8 magnitude or higher striking California. ‘The Big One’ earthquake will be 44 times stronger than the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994, which caused 72 deaths, about 9,000 injuries and an estimated $25 billion in damage in Southern California.

When and How Big Was the Last Big Earthquake in California?

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck on Wednesday, April 18 with an estimated magnitude of 7.9. The earthquake destroyed 28,000 buildings, claimed the lives of 3,000 people, and left over half the city’s population homeless.

On July 4 and 5, 2019, magnitude 6.4 and 7.1 earthquakes occurred in Ridgecrest and were felt throughout Southern California. The 7.1 magnitude earthquake was the largest earthquake in California in 20 years.

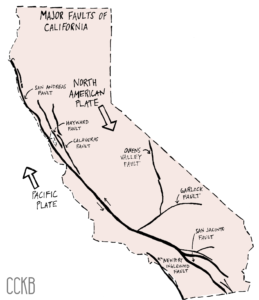

Major Fault Lines

When finding an apartment or house, we consider how much it costs, if the neighborhood is safe, if there are stores and restaurants nearby. We usually don’t consider a property’s proximity to a fault line.

This is most likely because very large ‘big one’ earthquakes don’t happen very frequently, and fault lines are out of sight, out of mind. But there are some major fault lines in California.

Movement occurs on both sides of each fault line. The overall rate of movement between the Pacific Plate and North American Plate is 2 inches per year on average.

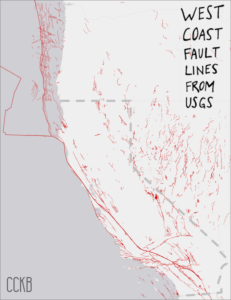

But it’s more complex: there are more than just a few major fault lines.

We build right on top of many of these fault lines, so it makes sense that we don’t think about them often because they’re hard to see.

Signs of Movement

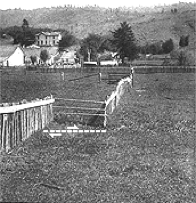

There are signs of them, if you know where to look. Ever see a sidewalk curb that’s offset like the one that was in Hayward, California before the city reconstructed the sidewalk? Or, ever see a fence that looks weird?

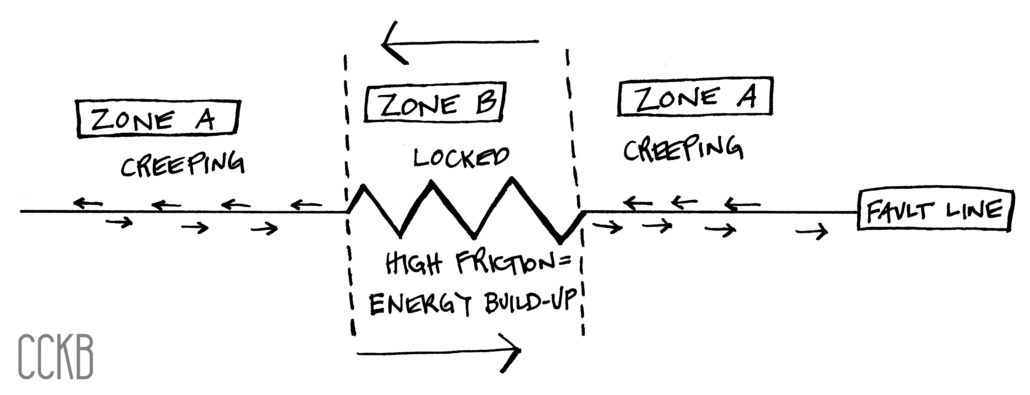

Sometimes, the movement along fault lines is slow and constant, similar to the growth of a fingernail. This type of movement is called creep. The rate of creep varies along and under the fault’s surface.

Other times the movement is sudden – that’s an earthquake. There are portions of the fault line that creep very slowly over time (Zone A), and there are portions that are locked and unable to move (Zone B).

Energy builds up at the locked locations over time until the energy exceeds the friction force between the two sides of the fault line, which results in the built-up energy releasing, and the fault slips.

After a slip, the fault line is now relaxed after the release of energy, and the build-up starts again.

Fault Line Cycles

Scientists can’t predict earthquakes, but they do know that the build-up of energy and release of energy happens in cycles. Each fault line has an approximate amount of time assigned to this cycle, which is called a return period or recurrence interval.

Peggy Hellweg, the Operations Manager for UC Berkeley Seismology Lab’s (BSL) network of earthquake data stations, describes how we obtain the data necessary to chart a fault’s return period:

“Scientists have been recording earthquakes all over the world since the early 19th century. BSL’s monitoring network alone includes more than 70 seismic stations and more than 30 geodetic stations in California.”

What about data for earthquakes that occurred before scientists started measuring with instruments?

Prehistoric Sleuthing

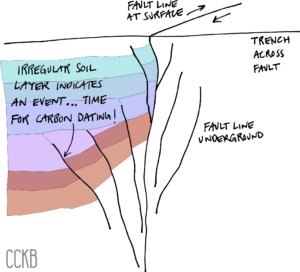

Hellweg explains, “Historical earthquakes are assigned magnitude based on written accounts of the earthquake, as well as information from the layers of rock and soil in the ground.

“Scientists dig trenches across a fault and compare the layers on each side of the fault, measure offsets and measure the age of the materials through carbon dating.

“From that, we can estimate the magnitudes, locations, and dates of earthquakes that happened before historical records – in California only around 250 years.”

History of the Hayward Fault and When Will a Big One Happen?

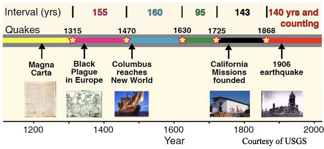

Data records from recent quakes, paired with data from historical and prehistoric sleuthing, results in the following timeline of earthquakes on the Hayward fault.

The chart tells us the average interval between large earthquakes is 138 years, plus or minus 30 years. Based on this average and standard deviation, the next large earthquake on the Hayward fault could be anywhere between 1977 and 2036, or even later, of course.

With a large interval between events, it’s easy to forget aboutearthquake preparation since most of us were not around for the last ‘big one’ earthquake.

Small earthquakes happen much more frequently, and they can serve to be a reminder for us to prepare.

Reviewed by Victoria Chames. Original publish date September 25, 2018.