September 19 marks the anniversary of not one but two major earthquakes in Mexico. One ranks as one of Mexico City’s deadliest disasters; the other demonstrates the importance of preparation and planning.

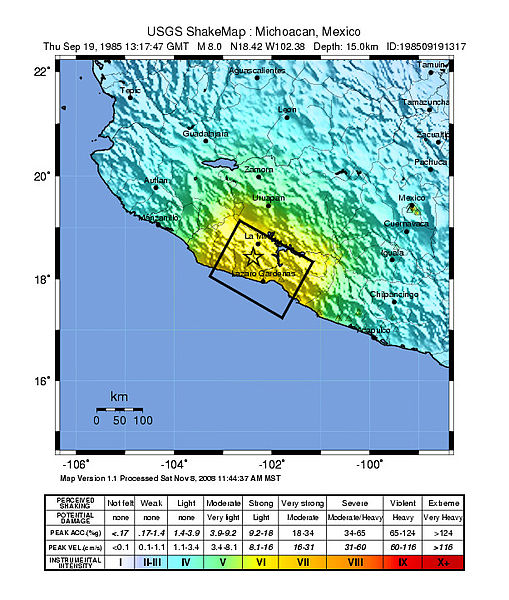

On September 19, 1985, a magnitude 8.0 quake cracked Mexico City apart, splitting highways and collapsing more than 420 buildings and hospitals. Casualty reports eventually settled on 10,000 people killed, but estimates range up to 60,000. Electricity, phones, and public transportation were down for several days. Assessed at a cost of $4-5 billion, the Michoacán earthquake quickly became a disaster of historical proportions.

32 years later to the day, on September 19, 2017, another large earthquake struck Mexico City, again splitting roads and collapsing buildings. That magnitude 7.1 quake, centered just south of the city of Puebla, had followed 12 days after a larger, magnitude 8.2 quake off the coast of Chiapas. The two September 2017 quakes killed 468 people and injured 6,300, yet the destruction and loss of life were nowhere near 1985 levels.

What were the big differences between September 1985 and September 2017

Emergency response

The first difference is the response of the government.

In 1985, President Miguel de la Madrid led an incompetent and corrupt response to the fatal earthquake, refusing international support, downplaying casualties, issuing a media blackout, and diverting emergency support to political allies. De la Madrid didn’t address the country until 36 hours after the event. Many Mexicans were forced to depend on grassroots rescue and aid organizations, sparking a social and political revolution that continues today.

By contrast, the 2017 earthquakes received powerful international relief efforts. President Enrique Peña Nieto immediately deployed 3,000 soldiers and visited a rescue site on September 19. Although criticism of the current government’s disaster response and reports of corruption continue, the coordinated efforts of 2017 were far superior to the government response of 1985.

Preparation and an early warning system

Inspired by the 1985 quake, Mexico’s CIRES (Centro de Instrumentación y Registro Sísmico) developed the world’s first early warning earthquake alarm. Using seismometers stationed along the Mexican coast, the system issues an alarm to Mexico City residents after detecting significant seismic movement. The system can provide up to 60 seconds warning before the effects of a major earthquake hit Mexico City.

The 8.2 Chiapas quake on Sept 7, 2017 kicked off the alarm, giving Mexico City residents considerable warning before the shaking started. Because the epicenter of the 7.1 Puebla quake on September 19, 2017 was so close to Mexico City, the alarm went off only a few seconds before citizens felt the effects.

The success of the early warning system for large quakes off the Mexican coastline gives hope to other earthquake-prone locations like Philippines, Ecuador, and the U.S. West Coast that face the similar risk of large earthquakes originating from offshore subduction zones.

Mexico City residents were also well practiced in proper earthquake response. On the morning of the September 19, 2017 quake, the entire city participated in its annual earthquake drill. The Puebla quake struck only two hours later.

Size matters (location, too)

Despite the early warning system, increased governmental transparency, tougher building codes, and the new culture of disaster preparedness that has arisen since 1985, the biggest reasons to explain the massive casualty difference between the two quakes could simply be magnitude and location.

Magnitude is a logarithmic scale, meaning each whole number in the scale is 10x the whole number before it. Using the USGS “How Much Bigger” calculator, we see that the 8.2 quake was about 12 times bigger than a 7.1 quake, and about 45 times stronger.

The 1985 earthquake, like most big Mexican earthquakes, occurred along the coast, where tectonic plates collide. The 2017 Puebla earthquake seems to have been caused by a “bend” in the North American plate that runs just south of Mexico City. Because the epicenter was much closer, the quake felt strong to city residents, but the overall strength of the 2017 earthquake was a fraction of the 1985 Michoacán quake.

Location and geography played a big role too. Mexico City sits above an ancient shallow lakebed, and the soil sediments trap the vibrations of earthquakes and send them reverberating around the basin.

In 1985, lower frequency waves traveling farther distances created a rolling motion in the ground that caused tall buildings to sway and fall. In 2017, the proximity of the epicenter to Mexico City created more intense shaking that affected smaller buildings. The location of the earthquake itself was a big reason why 2017 just wasn’t Mexico City’s next “big one.”